The Inquiry heard repeatedly how institutions prioritised their own reputations, and those of individuals within them, above the protection of children.

That’s what the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse published in their concluding report on Thursday. This was a statutory public inquiry held under the Inquiries Act.

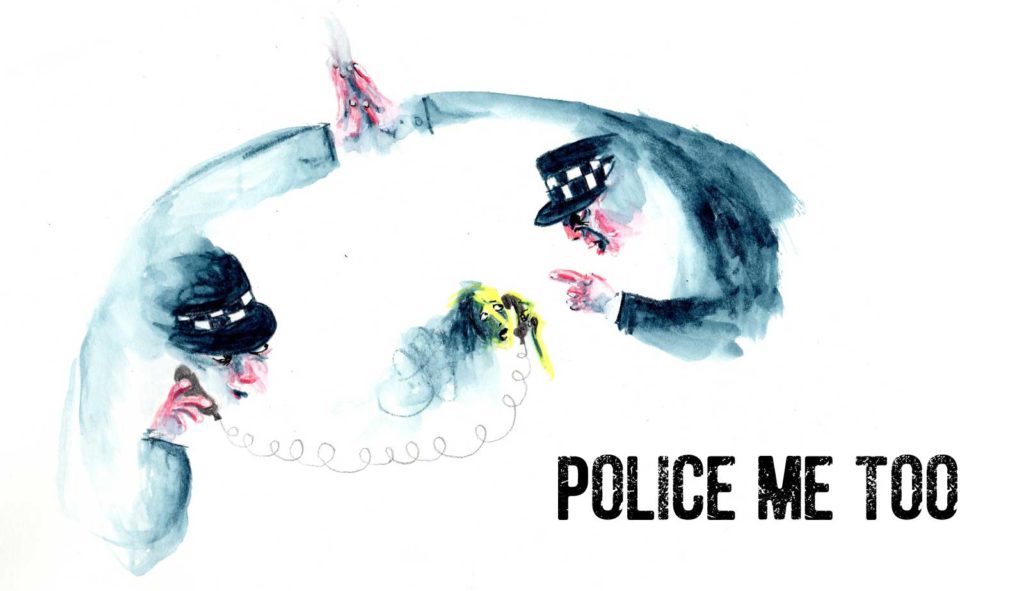

The police, though. They’re protectors, not perpetrators. We can trust them. Can’t we?

I’ve got a video interview. If you could watch it, you’d see a little boy. He’s at that age where he’s got no front teeth. Swinging his legs because he’s too small for his feet to reach the ground. He’s pulling at the threads in the arms of his school jumper. Nervous. Anxious. They’re talking about Playstations and the games he likes to play. They test him on his understanding between a truth and a lie.

The little boy discloses serious violence against him. He demonstrates with his hands how he’s been strangled, suffocated and stopped from breathing. By a police officer.

That little boy is my son. And it breaks me to think I didn’t protect him. I couldn’t protect him because I never knew. I never knew what he’d been through – for years – because the police refused to tell me what my son had said. They did nothing but cover it up. They didn’t protect my son, even though they knew. Who they did protect was the perpetrator. And, of course, themselves.

“We cannot have you bringing the force into disrepute.” “We will look after him.” Things I was told by officers of senior rank after I reported domestic violence and rape. It felt threatening. Like there would be consequences for me for speaking the truth about crimes, while seemingly no consequences for the police perpetrator who was committing them.

Five and a half years ago, I spoke out about my experiences at the launch of a new charity, the Centre for Women’s Justice. How the police officer pushed me out in front of a car when I was 5 months’ pregnant, so I was lying in the road directly in front of car headlights. He abused me physically, sexually, financially, psychologically. He knew what he was doing. Because he used to say I couldn’t do anything “because it has been 6 months”. He meant since the last incident but I didn’t know that then. He was talking about the time limit period that has recently been extended. After the talk, I said I wanted to find other women like me. Women abused by the police, instead of protected. Harriet asked me why. I don’t know, I said. For some kind of group action? I suspected I wasn’t the only one. I wondered whether there would be commonalities… themes. I’m autistic and I’ve always been looking at patterns. Perhaps I would see them in our stories.

The police, though. They’re protectors, not perpetrators. We can trust them. Can’t we?

When my story was shown on TV, serving and former police officers were posting online how I was a liar. They wrote that what I said couldn’t happen. It. Just. Couldn’t. Happen. They said police officer perpetrators were treated much more harshly than civilian perpetrators. That there was something wrong mentally with women like me, saying things like I did.

But other women came forward. Lots of women came forward. The Centre for Women’s Justice painstakingly pulled together the accounts to register a supercomplaint against police force responses to police perpetrated domestic abuse. That little seed sown at Bristol; nurtured by a young, talented journalist; planted by a TV network; fertilized by the Centre for Women’s Justice – well, it grew. The little seed became a forest that couldn’t be trodden on.

The three police regulatory bodies investigated and published the outcome in June. They determined the way police forces respond to these cases is significantly harming the public interest. Our police supercomplaint led to the most thorough review of this topic, ever undertaken in the UK to date. Isn’t that amazing?!

It’s not enough.

The data are incomplete. Apparently, the charging rates of police perpetrators are almost on a par with the charging rates of non-police perpetrators. But that might not be true. It’s skewed towards just two police forces. We have 43 police forces. Do you think it’s true?

We – the victims – told them we were concerned about corruption and collusion. The Centre for Women’s Justice told them the risk of lack of integrity was at the heart of their concerns. The report did acknowledge a concern among victims that forces ‘look after their own’ and may even retaliate against them. During the investigation, most police officers said they were confident that existing safeguards would deter and root out corruption and collusion. A focus group police officer (not police victim, police officer) said – and I quote – “victims feel the system will potentially protect their own or won’t be believed. It’s the complete opposite, but that seems to be a concern.” The report states the investigation had limited potential to uncover this. “In particular,” they said, “we recognised that improper manipulation of police processes may not be apparent to us in written records“.

So they don’t actually know because it was never looked into. And if it isn’t written down, it didn’t happen, right?

Because I’ve witnessed that in another institution. When Very Senior Management has an ‘agreement’ ‘not to put anything in writing’. I raised my concerns and resigned, by the way, but that’s another story.

And, in my own case, when I made a complaint, no records of me reporting the police officer could be found, allegedly. It’s as if it all never happened. But I still have the business card of the officer I spoke to.

So, instead, the report recommended that police forces should give more reassurance to victims. There, there dear. Calm down, dear. It’s all fine. Victims will be reassured about concerns of corruption and collusion when the opportunity to properly investigate our reasons lying behind them has been missed!

The police, though. They’re protectors, not perpetrators. We can trust them. Can’t we?

A core operational duty for the police is to protect life. But people are dying due to police unwarranted actions and omissions.

In the early hours of 9th July last year, a police crisis negotiator tricked me to stop me jumping. He didn’t tell me he was from the police. I told him about the police officer’s violence and how I couldn’t live anymore with the flashbacks of rape or how they’d covered everything up. Later that day and released from s.136 detainment, I arrived home to the news that PC Couzens had just pleaded guilty to Sarah Everard’s murder. Just two weeks later, Lydia, one of our women in the police supercomplaint took her own life. Only yesterday, a police officer was sentenced to 18 years and 3 months in prison for raping a girl under 13, several times, and perverting the course of justice. What will her life be like? Would she even have been listened to had it not been for the current focus on police?

They know the light is shining on their darkness. We need to brighten it. We cannot afford for this to become yesterday’s news. We need to find the way to a public inquiry on a statutory footing. Like the one just published on child sexual abuse. The three police regulatory bodies have determined – have they not – that the police responses in these cases is significantly harming the public interest.

The recommendations from the police supercomplaint don’t go far enough. I was disappointed by them, to put it mildly. One of them is to ensure that police forces follow existing regulations and statutory guidance.

That’s where we are. That’s how low the bar is. The recommendation is that our police forces ensure they adhere to the regulations and guidance already in place.

I’ll just repeat that. The recommendation is that the police should comply with the law in these cases.

Last summer, somehow I managed to report the police officer’s rape again. Despite me telling several police officers about this rape and another serious assault, in crisis incidents, not one of them took it any further. After reporting the police officer’s rape for a 2nd time, it was then left until earlier this year. They said it had been so long since they saw me, they’d have to come out and do it again.

I haven’t been able to let them come back. Because a couple of things happened in the interim.

First, I’d seen some of my data and saw the police had written that the police officer’s rape was unlikely to result in a prosecution. While I accept that may be true due to the appalling statistics, why write that before they’ve even taken a statement?

A few weeks after my acceptance speech at FILIA last October for the Emma Humphreys Prize for my work on police-perpetrated abuse, I was abused by a male police officer. He forced entry into my home. My PTSD was greatly triggered because what he did… and what he said… reminded me of the violent police officer I’d been married to. I called the police to register a complaint but they wouldn’t take the details. They said they’d be taken during a given appointment, that they then cancelled without even telling me.

After complaining about their failure to take details of my complaint, a male police officer was assigned to investigate the original complaint – without having any of the details.

My compaint was not upheld.

I then complained to the Police Standards Department. They wrote in an email how the police were “a family” – the very concerns we had raised in our supercomplaint. I then went to the Police and Crime Commissioner who upheld the review; my complaint had not been investigated appropriately or proportionately. It’s now back with the same Police Standards Department.

Not long after that, unexpectedly, I came across a video online. I clicked on it. Not knowing that it was of me! This was traumatic. It was my body in a suicide attempt. I’d had a PTSD episode due to the police officer’s rape and this male police officer had filmed me and put it on social media for likes. Thousands have viewed the video. It’s still there.

Considering all that I have shared here today, I decided to ask the police if my case could be investigated by an external force. I brought their attention to the recommendations made in the police supercomplaint outcome. I was open with them. I told them I had contributed to it and was asking in line with their recommendation. I didn’t have confidence in them.

Recommendation 2bii – it may be appropriate to refer a case for external force investigation when “victim trust and confidence cannot be secured another way“.

The police force said No.

The police, though. They’re protectors, not perpetrators. We can trust them. Can’t we?

No. Sorry, but I can’t.

Could you?

If the answer’s yes, imagine the senior officer in charge of your investigation is my ex-husband. Because the police force harboured him until his retirement.

I want a full statutory public inquiry into all UK policing.

Do you?

More cases are in the news now. Have you noticed that? It’s because the spotlight is on them, at last. The light is shining on the darkness. We need to amp it up; make it brighter; help the invisible to be seen. We need to be louder; make a noise; help the silenced be heard.

I want to finish with a thank you. To all of you. Everything you do makes a difference. And if you’re here today alone and don’t even speak to anyone, you’re still here. It is enough just to be present. It’s supportive.

Support women, support the world.

Root the violent and abusive police officers out.

Thank you.

[End]